Freedom of Expression in the Digital Space

A look at Malaysian legal issues around freedom of expression and privacy in the digital space

In recent months, the country has seen more instances of intervention from the Malaysian government on internet users, particularly members of the media, activists and politicians from the opposition party, who were brought in for questioning and/or charged after having expressed their views or published contents which are deemed to be showing dissent against the state and public authorities.

- Recent spike of cases show that Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 together with Penal Code and/or Sedition Act 1948 are widely used by the authorities to carry out investigations on purported offences carried out in the digital space.

- The Malaysian Courts are generally of the view that the laws used to restrict the freedom of expression are in line with the Federal Constitution.

- While the right to privacy is not provided by the Federal Constitution, it is nevertheless recognised by the Court that such right is included in Article 5(1) of the Federal Constitution as part of “personal liberty”.

- However, an individual is not able to rely on constitutional right to privacy against another individual. The tort of invasion of privacy is generally not recognised by the Court.

In a joint statement titled “CSOs Stand in Solidarity with Individuals being Silenced or Censored For Dissent” dated 19 June 2020, Centre for Independent Journalism (CIJ) had compiled a list of individuals/organisations that were called in for questioning and/or charged wherein majority of the investigations are in relation to publications made online, among others:

Members of the Media:

Human Rights Activists

- Siti Kasim

- Cynthia Gabriel - https://twitter.com/C4Center/status/1268772693098127360 ;

- R. Sri Sanjeevan

- Center to Combat Corruption & Cronyism - https://www.nst.com.my/news/crime-courts/2020/05/591890/health-minister-demands-apology-rm30mil-damages-c4-over-allegation

- Fadiah Nadwa Fikri

Opposition party members

- Hannah Yeoh

(Note : The Police has since identified a Pro-Perikatan Nasional portal to be responsible) - Hannah Yeoh

- R, Sivarasa

It is reported that these matters were investigated under Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998, many of which were also investigated with the combination of other laws, such as Section 505 of the Penal Code and Section 4 of the Sedition Act 1948.

Does Malaysian law recognise the right to free expression online?

Section 3(3) of the CMA states that “Nothing in this Act shall be construed as permitting the censorship of the Internet", whereas Section 6 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 defines “communication” as :

“any communication, whether between persons and persons, things and things, or persons and things, in the form of sound, data, text, visual images, signals or any other form or any combination of those forms”.

Therefore it could be inferred that the CMA 1998 recognises digital expression through communications, but with restrictions under sections 211 and 233.

Online users however often face challenges after having expressed views or published contents in social media platforms, as seen in the incidents listed above where investigations were made under Communications and Multimedia Act 1998, Sedition Act 1948 and Penal Code.

How do the Malaysian Courts view the laws?

Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998

Restrictions under Section 233 of the CMA is often seen as constitutional by the High Court, as seen in the cases of Syarul Ema Rena binti Abu Samah lwn Pendakwa Raya [2018] MLJU 1128 and Nor Hisham bin Osman v Pendakwa Raya [2010] MLJU 1249. The former concerns a purportedly indecent Facebook comment made against the then Prime Minister Najib Razak while the latter is in relation to an indecent comment made in a portal against the Sultan of Perak. In both cases, the High Court viewed Section 233 as a reasonable restriction which is compatible with the Federal Constitution. The charge against Syarul Ema Rena was later dropped. Article 19 had published an extensive legal analysis on the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998.

Section 4 of the Sedition Act 1948

In Public Prosecutor v Azmi bin Sharom [2015] 6 MLJ 751, two questions were referred to the Federal Court:

- whether s 4(1) of the Sedition Act 1948 contravenes art 10(2) of the Federal Constitution and is therefore void under art 4(1) of the Federal Constitution; and

- whether the Sedition Act 1948 is a valid and enforceable Act under the Federal Constitution.

The Defendant submitted that Sedition Act was invalid as it was made before Merdeka and not by the Parliament, the Act could not impose restrictions on freedom of speech and expression that were guaranteed under the Federal Constitution, since only the Parliament has the sole authority to make laws that could restrict the freedom under art 10(2). The Plaintiff submitted that Sedition Act was saved by art 162 of the Federal Constitution.

The Federal Court held that Section 4(1) of the Sedition Act did not contravene Article 10(2)(a) of the Federal Constitution and that the Sedition Act is valid and enforceable under the Federal Constitution.

Section 505 of the Penal Code

There is very little discussion on Section 505 of the Penal Code in the legal judgment database. An interesting point to note is that in Mat Shuhaimi bin Shafiei v Kerajaan Malaysia [2017] 1 MLJ 436, in which the Court of Appeal declared that Section 3(3) of the Sedition Act 1948 contravenes Article 10 of the Federal Constitution and therefore is invalid and of no effect in law, The Court of Appeal viewed Section 3(3) of the Penal Code to be in conflict with Section 505 of the Penal Code. The Court of Appeal opined that Section 505 of the Penal Code requires “intent” to be an essential ingredient to be proved, whereas Section 3(3) of the Sedition Act displace the proof of intent, when these two sets of law could be resorted to in a similarly circumstanced situation. The Federal Court however set aside the Court of Appeal’s decision on the grounds that the civil application filed by Mat Shuhaimi to challenge the constitutionality of Section 3(3) is an abuse of the court process because Mat Shuhaimi had previously been unsuccessful in striking out Section 4 of the same Act.

Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984

One of the concerns with this Act lies with the power of the Home Affairs Minister. Printing license and publishing permits can only be approved by the Home Affairs Minister and the Minister may at any time revoke or suspend a permit for any period he considers desirable.

The High Court in Mohd Faizal bin Musa v Minister of Home Affairs [2017] 11 MLJ 397 recognises the Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984 as one of the statutory provisions enacted pursuant to the provisions of art 10(2)(a) of the Federal Constitution which aims to limit freedom of expression of individuals on the grounds, inter alia, prejudicial to public order as stated under s 7(1) of PPPA. Even though this decision is overturned by the Court of Appeal in Mohd Faizal bin Musa v Menteri Keselamatan Dalam Negeri [2018] 3 MLJ 14, the Court of Appeal nevertheless shared the same view :

“While art 10 allows the right to freedom of speech and expression. However, as rightly said by the learned High Court judge and submitted by learned senior federal counsel, the rights conferred under the articles are not absolute as under cl 2 of art 10, Parliament is empowered to restrict these rights through the provisions of the law and Act 301 is one of the laws enacted pursuant to that restriction which aims to limit freedom of expression, inter alia, in the interest of the security of the Federation and public order. Therefore the validity of the law ie sub-s 7(1), is not in question here. What is to be determined is whether, applying the factual matrix of the instant case, the order is validly made.”

The Federal Court in Public Prosecutor v Pung Chen Choon [1994] 1 MLJ 566 dealt with the constitutionality issue of Section 8A of Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984.

Section 8A read as follows:

8A. (1) Where in any publication there is maliciously published any false news, the printer, publisher, editor and the writer thereof shall be guilty of an offence and shall, on conviction, be liable to imprisonment for a term no exceeding three years or to a fine not exceeding twenty thousand ringgit or to both.

(2) For the purposes of this section, malice shall be presumed in default of evidence showing that, prior to publication, the accused took reasonable measures to verify the truth of the news.

(3) No prosecution for an offence under this section shall be initiated without the consent in writing of the Public Prosecutor.

Four questions were posed to the Federal Court:

- Whether s 8A(1) of the Act read with s 8A(2), imposes restrictions on the right to freedom of speech and expression conferred by art 10(1)(a) of the Constitution?

Federal Court answers in the affirmative. Section 8A(1) of the Act does impose restrictions on the right to freedom of speech and expression conferred by art 10(1)(a) of the Federal Constitution.

- If so, whether the restriction imposed is one permitted by or under art 10(2)(a) of the Constitution.

- Whether s 8A(1) of the Act, read with s 8A(2), is consistent with art 10(1)(a) and (2)(a) of the Constitution and therefore, valid.

The Federal Court had also made an observation that Article 10 “enumerates the three Rights available to citizens only; namely, the Right to freedom of speech and expression, the Right to assemble peaceably and without arms, and the Right to form associations”.(Emphasis added)

The Federal Court answered both Qs 2 & 3 in the affirmative.

- Whether s 8A(2) of the Act, by presuming false news per se to be malicious, amounts to pre-censorship and accordingly, contravenes art 10(1)(a) and (2) of the Constitution.

No. The Federal Court viewed the statutory presumption of malice upon proof of falsity of news published in Section 8A(2) as a way to assist the prosecution, and cannot be said to be equated to pre-censorship which takes place before publication. Furthermore, “Section 8A(2) does nothing to restrict freedom of the press either directly or indirectly. On the contrary, by providing for the rebuttal of the presumption of malice upon proof by the accused that he had taken reasonable measures to verify the truth of the news concerned before its publication – a standard practice of responsible journalists – it promotes and ensures that freedom of the press is neither abused nor exploited.”

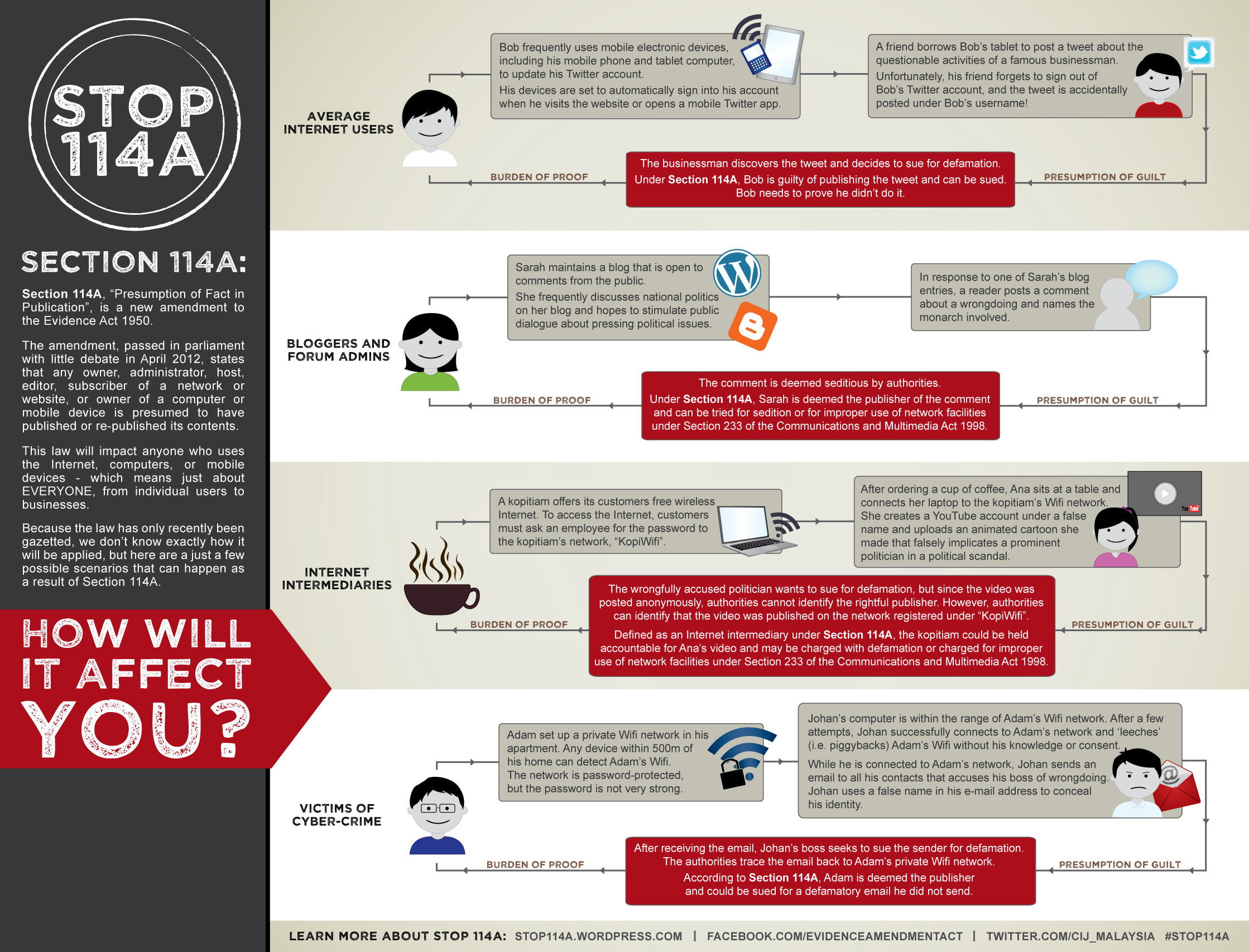

Section 114A of the Evidence Act 1950

This is a controversial section which came into force on 31 July 2012 as an amendment to the Evidence Act 1950. Under this section, the law creates a presumption of fact that an internet user is deemed to be a publisher of a content under three circumstances, under proven otherwise. Section 114A reads as follow:

“Section 114A: Presumption of fact in publication

(1) A person whose name, photograph or pseudonym appears on any publication depicting himself as the owner, host, administrator, editor or sub-editor, or who in any manner facilitates to publish or re-publish the publication is presumed to have published or re-published the contents of the publication unless the contrary is proved.

(2) A person who is registered with a network service provider as a subscriber of a network service on which any publication originates from is presumed to be the person who published or re-published the publication unless the contrary is proved.

(3) Any person who has in his custody or control any computer on which any publication originates from is presumed to have published or re-published the content of the publication unless the contrary is proved.

(4) For the purpose of this section:-

(a) “network service” and “network service provider” have the meaning assigned to them in section 6 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 [Act 588]; and

(b) “publication” means a statement or a representation, whether in written, printed, pictorial, film, graphical, acoustic or other form displayed on the screen of a computer.”

This section goes against the fundamental principle of “innocent until proven guilty”. It reverses the burden by imposing a burden on a person to prove his innocence, as opposed to the prosecution to prove that the accused is guilty.

The impact of Section 114A to internet users can be explained in this infographic:

Source: https://stop114a.files.wordpress.com/2012/07/stop114a-infographic1.jpg

Section 114A has been used in defamation suits concerning emails and Facebook posting. In the High Court case of Thong King Chai v Ho Khar Fun [2018] MLJU 357, the Court found a presumption of fact that the Email was published by the Defendant as it had originated from his email address and that the the Facebook Posting was published by the Defendant through his Facebook account, pursuant to Section 114A. This presumption of fact is admitted by the Defendant.

The High Court in Tong Seak Kan & Anor v Loke Ah Kin & Anor [2014] 6 CLJ 904 stated that Section 114A(2) can be applied retrospectively. However, in a criminal case, the High Court in Rutinin bin Suhaimin v Public Prosecutor [2014] 5 MLJ 282 stated that section 114A does not apply to the instant case as the offensive remark was posted before 31st July 2012.

Liability was also imposed on website owners for postings made by users of the website. In Stem Life Bhd v Mead Johnson Nutrition (M) Sdn Bhd & Anor [2013] MLJU 1582, not only the was the website owner found responsible for the postings made by third parties, the website owner was also found to be responsible over a hyperlink which redirects readers to an external blog which was also defamatory to the complainant. The High Court further compared a website owner’s role to a newspaper editor :

“Therefore, in my judgment, Mead Johnson's role is akin to that of an editor of a newspaper. It is common knowledge that some newspaper editors choose to review the letters written to them (and perhaps edit the letters) before publishing them whereas some newspaper editors choose to publish the letters on an "as is" basis. Either way, the law is clear, the editors, (and the newspaper) would be liable in the event that the contents of the letters are found to be defamatory.”

In the recent contempt of court proceedings filed by the Attorney General against Malaysiakini and its editor-in-chief in the Federal Court over comments made by readers against the judiciary, the Respondents sought to set aside the leave granted by the Federal Court to the AG. In refusing the Respondents’ application, the Federal Court is of the view that a prima facie case that the Respondents are presumed to have published the impugned comments, has been made out, by virtue of Section 114A. (prima facie = based on first impression, at the first appearance)

At the time of writing, we have yet to see a constitutional challenge on this section being reported.

Can I protect my privacy in the digital space?

The Federal Constitution does not explicitly provide for the right to privacy. However, the Federal Court in Sivarasa Rasiah v Badan Peguam Malaysia & Anor [2010] 2 MLJ 333 inferred that such right exists under art 5(1) of the Federal Constitution : “It is patently clear from a review of the authorities that ‘personal liberty’ in art 5(1) includes within its compass other rights such as the right to privacy.”

In Lew Cher Phow @ Lew Cha Paw & Ors v Pua Yong Yong & Anor [2011] MLJU 1195, a dispute between neighbours concerning the Defendants’ CCTV facing the house of the Plaintiffs. The High Court found in favour of the Plaintiff and stated in the conclusion that : “The right to privacy is a fundamental human right. On the peculiar facts of this case, the right to privacy consists of the plaintiffs' right to private and family life and home. This is a basic right and need which everyone cherishes and holds dear. The well known saying that a man's home is his castle holds true. In holding the balance between privacy and safety, the Court must strike in favour of privacy in the particular circumstances of this case.”

However, it appears that there are conflicting views on the tort of invasion of privacy. The High Court in Lee Ewe Poh v Dr Lim Teik Man & Anor [2011] 1 MLJ 835 found that the invasion of privacy rights was actionable under our common law. However, in John Dadit v Bong Meng Chiat & Ors [2015] MLJU 1961, the High Court held that the tort of invasion of privacy is not recognised by the Malaysian laws. Furthermore, it was decided that the Federal Constitution as a branch of public law, does not extend its provision to infringements of an individual’s right by another individual.

It is not to say that there is no avenue for victims of infringement of privacy. In Pendakwa Raya lwn Nor Hanizam bin Mohd Noor [2019] MLJU 638, the accused was charged and found guilty under Section 509 of the Penal Code which deals with offences that relate to word or gesture intended to insult the modesty of a person. Section 509 reads as follows:

- Word or gesture intended to insult the modesty of a person

Whoever, intending to insult the modesty of any person, utters any word, makes any sound or gesture, or exhibits any object, intending that such word or sound shall be heard, or that such gesture or object shall be seen by such person, or intrudes upon the privacy of such person, shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to five years, or with fine, or with both.

The accused was charged for recording a female in the act of showering without her knowledge using a handphone. He thereafter spread the video to WhatsApp group which includes the victim. Similarly in Maslinda bt Ishak v Mohd Tahir bin Osman & Ors [2009] 6 MLJ 826, a RELA officer was charged and pleaded guilty under Section 509 for taking pictures of a woman urinating.

The High Court case of Toh See Wei v Teddric Jon Mohr & Anor [2017] 11 MLJ 67 specifically deals with email. The Plaintiff alleged that his email account was hacked by the the first Defendant who then published the content of his email which subsequently caused the Plaintiff’s dismissal. The Plaintiff premised his claim on the torts of invasion of privacy and breach of confidence. The High Court found that the recognition of constitutional right to privacy “may not be enforced by an individual against another individual for the infringement of rights of the private individual as Constitutional Law will take no recognisance of it.” On the issue of tort of invasion of privacy, the High Court did not make a ruling but stated that “It is also recognised by this court that all the cases recognised the tort of invasion of privacy is limited to matter of private morality and modesty in particular women.”

The High Court in this case found that the Plaintiff did not come with clean hands and as such equity cannot afford protection to the Plaintiff, who had emailed to his friends some negative remarks about the Defendants. The Plaintiff also loses his substantive due process of right to privacy once the information is revealed to a third party. There is further no evidence to show that the Defendant involved in the hacking of the emails.

Other than Section 509 of the Penal Code which strictly deals with actions which insults the modesty of a person, there is no statutory law that guarantees a Malaysian citizen’s right to privacy. The closest we have is Personal Data Protection Act 2010, but it concerns personal data and in commercial transactions only.

Calls for Reform

Several local and international civil societies have urged the government to reform or repeal the controversial laws which were often seen to be used to silent critics. While the previous PH government had pledged to reform several laws including Printing Presses and Publications Act, Sedition Act, Prevention of Crime Act and the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act, we have yet to observe whether the reforms will be continued by the current PN government.

This update is also available as PDF

About Author

Kelly Koh is an Advocate & Solicitor (non-practicing) and member of English and Malaysian Bar with experience in general litigation practice. She looks after Sinar Project's administrative, finance and compliance procedures, while also providing legal counsel to the organization.