Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) Southeast Asia Regional Workshop

Workshop report for for Open Observatory for Network Interference (OONI) Southeast Asia Regional Workshop 2018, on running OONI Probe tests with our local partners from Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam.

2018 November - Report prepared by Lara Powell, Khairil Yusof and Nawel Zribi

Key Findings

-

OONI Probe, operated through Raspberry Pi devices, presents an effective, affordable and user-friendly method for regular and comprehensive monitoring of network interference for digital rights activists and NGOs in Southeast Asia. It is complementary to OONI Probe mobile app.

-

Individuals planning to monitor (and/or report on) online censorship must consider the risks of doing so for their particular context. A variety of precautions can be taken to limit the risks associated with using OONI Probe.

-

Raspberry Pi, as a general purpose portable Linux computer, can also be used for a variety of tasks such as monitoring for malware, VPN or TOR proxy, secondary device to write and store sensitive reports and media, and more; this can be explored in future workshops by Sinar Project or other digital rights and security partners in the region.

Introduction

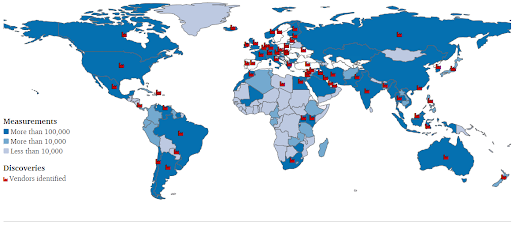

Map showing southeast Asia countries

Southeast Asia is facing growing concerns regarding the repression of freedom of expression online; network interference is a key means by which this repression is occurring. The Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) provides a platform for the detection of internet surveillance and traffic manipulation, and works to inform the availability, reliability and security of the Internet in Asia-Pacific. Help from regional partners is needed, in order to monitor and report on internet surveillance and network interference. The deployment of network monitoring nodes will provide evidence of network interference in a region that has serious concerns regarding network interference restricting freedom of expression online.

Background

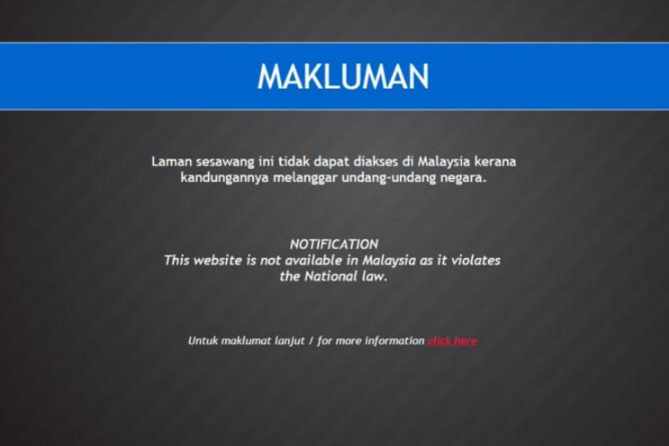

Blocked website in Malaysia

The situation of repression of freedom of expression online is escalating in Southeast asia. An ethnically, politically, and linguistically diverse region, Southeast Asia includes Brunei, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor-Leste, and Vietnam. There were over 370 million internet users in the region in 2017, representing an increase of over 30% from the previous year [Digital Southeast Asia 2017 Report].

Since July 2015, the Malaysian government has blocked various websites, including online news portals and private blogs, for reporting about the scandal surrounding Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak over his mysterious private dealings with RM2.6 billion [EFF Deeplinks 2015]. While the aforementioned sites are now no longer blocked, through the use of OONI Probe Sinar Project recently detected censorship of websites serving the LGBT community, among others [Online LGBT Censorship Malaysia].

Recently, the situation regarding online censorship has worsened in Indonesia. Web content is frequently blocked for violating laws as well as social norms. A variety of web content is openly targeted, alongside unacknowledged blocks on content relating to Papua and West Papua [Freedom on the Net 2017]. 2017 Amendments to the problematic Information and Electronic Transactions (ITE) law made the situation worse, by empowering officials to directly block prohibited electronic information. According to Freedom House, there are no major obstacles to open and free private discussion, however blasphemy and defamation laws may inhibit the expression of views on “sensitive topics”, including on social media [Freedom in the World 2018].

In Thailand, censorship and rights violations intensified after the death of King Rama IX in October 2016, with authorities banning over 1,000 websites. The amended Computer Related Crimes Act (CCA) passed in January 2017, grants the authorities more powers to block and remove offending content [Freedom of the Press 2017].

In Philippines, Internet freedom declined in 2017, even though access improved. Mobile service shutdowns were implemented, content manipulation and cyberattacks threatened to distort online information. The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism had its website hacked after publishing a report about Duterte’s war on drugs, which has resulted in thousands of extrajudicial killings. Also, since mobile phones remain the most widely used wireless communication tool, mobile service shutdowns were reported in some major cities during Major Sinulog events in January 2017. Freedom on the Net 2017]

In Cambodia, despite constitutional guarantees of press freedom, the media are tightly controlled by the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) and its allies. A telecommunications law that took effect in December 2015 gave the government sweeping powers to monitor personal communications and punish speech on national security grounds. [Freedom of the Press 2017].

The Constitution in Vietnam, amended in 2013, affirms the right to freedom of expression, but in practice the Vietnamese Communist Party has strict control over the media. Legislation, including internet-related decrees, the penal code, the Publishing Law, and the State Secrets Protection Ordinance, can be used to fine and imprison journalists and netizens. The new government under Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc, in power since mid-2016, has made no attempt to improve the environment for internet freedom. After the release of some bloggers as Vietnam negotiated the TPP agreement, arrests ramped up in the second half of 2016. By April 2017, at least 19 individuals were in detention for online activities. Blogger prosecutions intensified in 2017, culminating in a 10-year prison sentence for the activist using the pen name Mother Mushroom. Civilian groups attacked bloggers and police obstructed protests organized using digital tools. [Freedom on the Net 2017].

Clearly, action needs to be taken to monitor and respond to the concerning situation regarding freedom of expression online in Southeast Asia. The deployment of network monitoring nodes, via OONI, would allow for continuous objective technical monitoring for network interference. OONI Probe tests could provide the necessary evidence of network interference to support advocacy for government transparency, freedom of expression and access to information.

By training partner organizations on the use of OONI Probe, we aim to inform the availability, reliability and security of the Internet in Asia-Pacific. We hope to support the development of the research community by encouraging the collection and publication of online public data collected from a variety of node tests (to be published on OONI Explorer). Moreover, the workshop was intended to improve existing OONI network interference tests through input from local research partners in regard to local network conditions and constraints.

Workshop

Sinar Project's coordinator Khairil Yusof explaining ooniprobe during OONI Workshop

On October 23 2018, Sinar Project hosted a regional workshop on testing and collecting evidence of network interference, which aimed to increase and improve monitoring of internet censorship in Southeast Asia. Five participants attended the workshop, including activists, journalists and partner organization representatives from Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia, Cambodia, and Vietnam. The workshop taught the participants how to access and update country URL test lists (i.e. through Citizen Lab/Github), as well as how to run OONI probe tests to monitor network interference.

OONI Probe can be run from desktop, mobile and hardware platforms. Each approach provides, different benefits as well as limitations.

Network Censorship

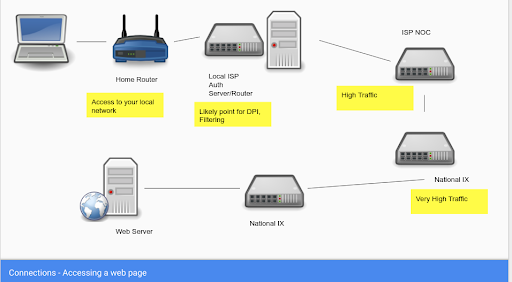

A brief introduction on how a typical Internet connection works from router to Internet Exchange Point (IXP) was covered as well as common methods of censorship or interference such as DDOS, DNS Redirection or Hijacking, Deep Packet Inspection and Filtering.

Internet connection process as explained during the OONI Workshop

OONI Probe Tests on Raspbian

Workshop participants learned how to run OONI Probe on Raspberry Pi for reasons relating to convenience, security and affordability (see more on this below). Each participant received a Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+ — a small, discrete device which is a fully functional computer. Participants learned how to configure Raspbian on the device using Etcher. After installing OONI Probe on their Raspberry Pi, participants are now able to run Web Connectivity tests (which examine whether and how websites are blocked), HTTP Invalid Request Line tests (which monitor for “middleboxes”), and HTTP Header Field Manipulation (similar to the previous test, but with different methodology). They also learned how to configure OONI Probe to start automatically.

OONI Probe Mobile App and Running Censorship Testing Campaigns

In addition to learning how to run OONI Probe on Raspberry Pi, the participants learned how to use the OONI Probe mobile app. The current version of the app only tests random urls from global and local test-lists, it includes two speed tests which are not currently available for OONI Probe on desktop or Raspberry Pi’s. These tests (NDT and DASH) allow users to collect data that may be useful for examining potential net neutrality violations and cases of throttling.

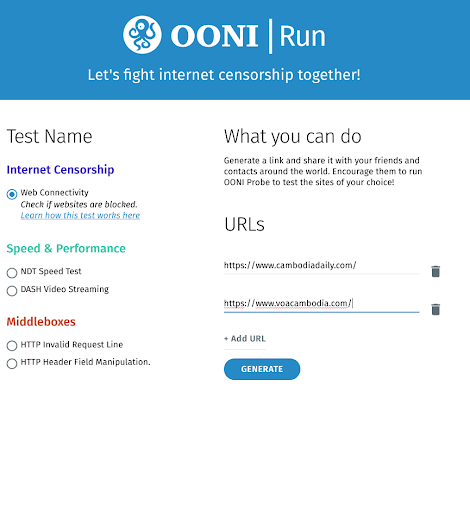

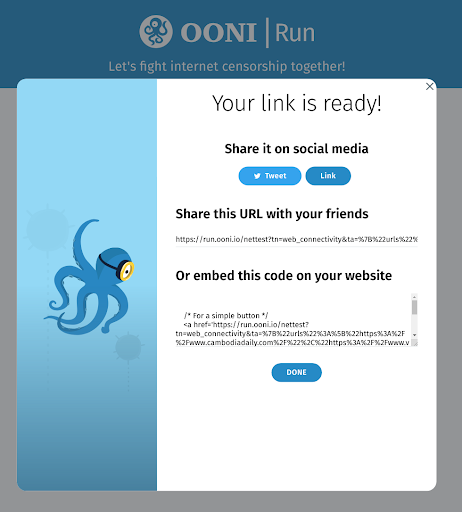

OONI Run

The mobile app is also very useful for crowdsourcing tests with OONI Run feature during events such as elections and protests. The participants learned how to use OONI Run to generate a link which they can share with their friends and contacts; anyone who has the OONI mobile app can simply click on the Ooni Run Link and Web Connectivity tests will run. Thus, organizations and activists can run online campaigns (on their webpage or Twitter, for example) in order to get a comprehensive, large pool of evidence of network interference during a short period of time, in which sites that are reported to be blocked and methods may change rapidly as the situation on the ground.

We shared lessons learned of experiences from previous campaigns covering Malaysian and Cambodian elections.

If participants were to run campaigns, workshops should be done in advance of potential events, with local activists, civil society and media partners so that they have OONI App installed and briefed on how to run and report tests.

OONI Run Shareable internet censorship tests links

Citizen Lab Tests Lists

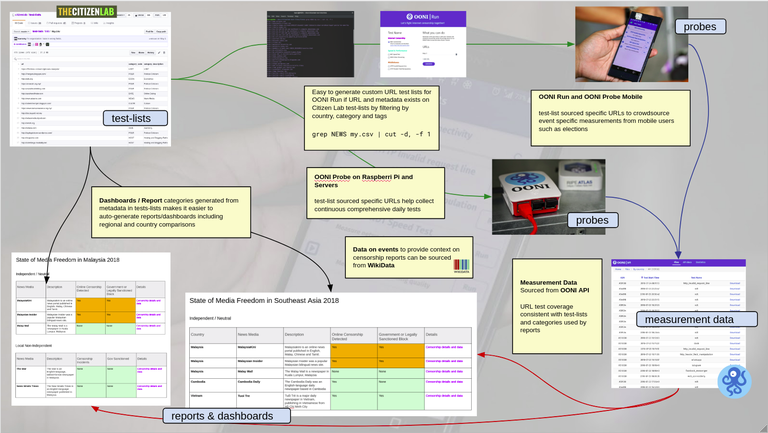

Uses of Citizen Lab Tests Lists

Citizen Lab maintains test lists of URls, which are intended to help those testing internet censorship. As the OONI probe source of URls to test and Sinar Project’s Censorship Dashboard uses these lists to generate reports based on list categories, a goal of the regional workshop was to inform participants about these lists and how update them. Due to their regional expertise and knowledge, participants can provide feedback on which URLs to monitor, which features and information that would be useful for their work, and if the existing urls are up to date or accurate.

Understanding Risks

Also highlighted was the importance of being aware of the potential risks associated with testing for internet censorship. For the most part, in Southeast Asia, it is legal and relatively safe to test for network interference (although “legal” does not always equate to “safe”). Testing for network interference can often be framed as “research” — a non-political, and therefore generally non-objectionable, action. However, this is not always the case. For instance, in Vietnam it is illegal to even attempt to access certain “sensitive” information (see “Country-Specific Risks” below). In general, it is important to be aware of potential risks even in contexts which are thought to be “free” and “safe”; for example, if there are broadly defined laws in place, there is room for interpretation and abuse.

To our knowledge, no individual or group has faced serious repercussions as a result of running OONI Probe, however workshop participants were advised that: anyone monitoring their Internet activity would know that they are running OONI Probe; OONI’s “HTTP invalid request line” test could be viewed as a form of “hacking”; and the use of OONI Probe might potentially be viewed as illegal or anti-government activity (Summary of Potential Risks of Using OONI Probe). Methods for circumventing risk were discussed, including making informed decisions regarding types of tests to run, privacy settings, how to upload data and platforms for running OONI Probe.

The workshop also addressed the potential risks of reporting on the results of OONI Probe tests. Reporting generally poses a higher level of risk than simply running tests. In certain contexts in Southeast Asia, it may be legal/safe to test for network interference, but not legal/safe to publicize or comment on the findings. The workshop participants were encouraged to familiarize themselves with the risk level in their country and decide accordingly. Whether or not they report on their findings, the data collected from network interference testing is valuable. If someone runs a test but is unable/unwilling to report on their findings, a journalist or activist in a safer place or situation may report on their behalf. OONI Probe data provides evidence of censorship events, supports transparency of global internet controls, allows researchers to conduct independent studies and to explore new research questions, and allows for public verification of findings. This is in line with Sinar Project’s goals relating to Open Data (https://sinarproject.org/open-government/open-data).

Findings

OONI Explorer internet censorship measurement tool

Regional Risks:

By bringing together partners from different countries across Southeast Asia, the workshop uncovered some general trends relating to the risks of internet censorship monitoring. After evaluating participants’ awareness and tolerance of risks associated with OONI Probe, we learned that uncertainty of local risks is a key barrier to monitoring (and reporting on) network interference. Ambiguous laws and policies can be more of a deterrent than clear laws prohibiting Internet censorship testing.

For instance, the participant from Cambodia expressed uncertainty regarding the risks of running OONI Probe in his country and, as a result, was hesitant to run tests. Broad and unclear legislation, such as that which allows for persecution on the basis of “national security” grounds, is open to abuse in Cambodia; therefore, it is unclear what repercussions may result from running OONI Probe or reporting on results of network interference tests. Conversely, the workshop participant from Vietnam is willing to run OONI Probe, despite the possibility of severe sanctions for doing so; the legal repercussions for online “activism” of all sorts are very harsh, but very clear, thus the participant knows exactly what risks he is facing and can take steps to circumvent these risks.

Country-Specific Risks:

Vietnam

The risk associated with using OONI Probe is very high in the surveillance state of Vietnam. It is illegal to attempt to access certain information and to collect government data, therefore running an OONI Probe test is forbidden by law and sanctions could be applied.

Responding to Risk

Methods for circumventing the aforementioned risks were discussed, including the possibility of running OONI Probe in a public place, on public wifi (therefore on a public IP address). For instance, an OONI Probe test could be deployed in a mall or an internet cafe (which doesn’t have surveillance cameras). Another method which was proposed was to use a VPN with an IP address in another part of Vietnam - however, this of course would put someone else at risk and is therefore not advised. Hiding microSD card for Raspbian image and OONI Probe was also discussed as an advisable precaution; it can be easily hidden in the event of a raid, or other security threat, in addition to the Raspberry Pi itself. In general, the discussion highlighted the importance of planning for risks and taking into account complex contextual factors when planning to use OONI Probe.

Cambodia

The participant indicated that, to his knowledge, it is safe to access/collect information in this country (i.e. it is safe to run OONI Probe), but there are risks associated with critiquing information/creating content (i.e. reporting on OONI Probe test results). Indeed, in Cambodia, despite constitutional guarantees of press freedom, the media are tightly controlled by the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) and its allies. A telecommunications law that took effect in December 2015 gave the government sweeping powers to monitor personal communications and punish speech on national security grounds. [Freedom of the Press 2017].

Thailand

The participant indicated that the situation is similar to that described above regarding Cambodia; it is safe to run OONI Probe but there is uncertainty around potential risks of reporting on the collected data. The amended Computer Related Crimes Act (CCA) passed in January 2017, grants the authorities more powers to block and remove offending content [Freedom of the Press 2017].

Malaysia, Indonesia and Philippines:

There are minimal risks associated with testing for network interference in these countries. Testing and reporting is permitted, however there is still the risk that the respective governments will abuse existing laws to apply sanctions (e.g cyberbullying and cybercrime laws, among others, are open to abuse).

Other benefits of the Raspberry Pi 3 B+

The Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+ is a small single-board computer that poses many benefits and opportunities. It is a practical platform for running OONI Probe and other network interference tests; as a fully functional Linux computer, it also has various other functions.

Many of the possibilities it presents are particularly beneficial for activists and journalists working on Internet Freedom and Digital Rights.

Affordability

- Cost: The device is only $40 USD, therefore presenting a highly affordable (thus accessible) device for running OONI Probe.

- Energy consumption: it takes a minimal amount of electricity to keep OONI Probe running 24/7 which was the purpose of having this probe vs mobile device

Practicality

- Portable: The device itself is easy to transport since it is small, light and inconspicuous

- Secure:

- Discrete: The fact that the device is small and discrete in appearance presents benefits for those who have concerns for their security

- Data storage: Micro SD format for loading operating system and data storage; this has practical/technical benefits as well as benefits for digital security (i.e. easy to hide and protect sensitive data)

- Multipurpose:

Additional software or other custom operating systems can be installed for a variety of other purposes for activists working with other partners - Network traffic and network analysis tools

- Anonymity and censorship circumvention tools

- Digital security and forensics tools and distributions such as Kali Linux

Other benefits

Once connected to a monitor/projector, a keyboard and a mouse, the device could be used for several purposes :

- Internet access, communication and entertainment (e.g: Youtube, social media, …)

- Educational and entertainment tool for kinds (e.g: educative apps and games)

- Training tool for organisations and community centers

- As an alternative to computers and laptops for low income families, teenagers, students and young workers.

Raspberry Pi running Raspbian Desktop and OONI Probe

Conclusions/Recommendations

- We would like to call on all activists, journalists and anyone inclined and capable to help contribute to internet network interference monitoring in Southeast Asia.

We need your help with: - Updating URL test lists

- Running censorship testing campaigns and workshops

- Deploying OONI Probe tests

Project Lead & Engineer Arturo Filastò's quote

Contact Us to get involved!

- We recommend OONI Probe on a Raspberry Pi device as an effective, affordable and practical way for activists and partner organizations to contribute to consistent daily measurements for network interference in the South East Asia region, but also to run other other tests or software for digital security research.

- It is important to consider your risk environment and risk tolerance before using OONI Probe or reporting on OONI Probe test results.

Funding and Support

This workshop was possible with the kind support and funding of Open Technology Fund and ISIF.Asia

Appendix

Resources

- Workshop slides

- OONI website

- OONI Run

- Guide for installing ooniprobe on Raspberry pi devices: lepidopter install guide

- Guide for installing ooniprobe on unix based systems: installation guide

- Citizen Lab Test Lists

- OONI Test List methodology

- The Tor Project on Twitter

- Freedom House Report: Freedom on the Net 2017

Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+ specifications:

- Processor: Broadcom BCM2837B0, Cortex-A53 64-bit SoC @ 1.4GHz

- Memory : 1GB LPDDR2 SDRAM

- Connectivity 2.4GHz and 5GHz IEEE 802.11.b/g/n/ac wireless LAN, Bluetooth 4.2, BLE

- Gigabit Ethernet over USB 2.0 (maximum throughput 300Mbps)

- 4 × USB 2.0 ports